Getting rubbish off the island, especially when doing renovations, is a time‑consuming business. There are decades’ worth of things that ‘could come in handy’ on Erraid. The purge we are undertaking is for those things that obviously haven’t come in handy for at least 20 years: old fishing tackle, knackered creels, rope, ripped life jackets, rugs, underlay and bathroom tiles. To get rid of it all, we have to wait for a low spring tide, load everything onto a tractor, and drive it across to the other side of the estuary, where the minibus waits to be stuffed to the gills. Last time we needed a lot of stuff taken to the tip, we paid someone to do it. Today, we are experimenting with the economy of doing it ourselves.

It’s 8.30am. We boat over to the bus. The sea is choppy and we risk enduring the whole trip with wet trousers. We shuffle to the back of the boat, which gives us just enough lift at the front to ride the waves.

It’s a one hour and fifty minute trip up to the Tobermory recycling centre. Armed with Archie, Marianne and a Bluetooth speaker, I set off, stopping at Miek and Rutger’s place so they can load a sink and toilet into the back and save themselves a trip. Inside, the minibus smells of foetid undergrowth where aerobic respiration has clearly faltered, so despite the biting cold, the windows are open. I remember that, despite my best efforts, the two outer rear tyres are looking flattish, so we stop at Robin’s garage to see if he can put some air in them and to fill up with fuel. As an old local once said to me, you should treat a half‑full tank as empty around here.

Robin has a compressor, but only a front‑on nozzle attachment. I need a 90‑degree nozzle, so Archie is tasked with putting five minutes’ work in with the foot pump. Neither of us is convinced it’s making any difference. Robin then uses a customer’s car to power our very short‑cabled mini‑compressor, but stops after a few minutes as he doesn’t want to blow a fuse on a car that’s there for something entirely unrelated. We nod and see his point. I’m sanguine about completing our task anyway, as there are dual tyres on the back. I still stop at the garage in Craignure to see if they can take a look. They tell me to come back in the afternoon, once we’re done up north.

The Mull Chocolate Shop is open—a rare treat. I’ve been wanting one of their millionaire shortbreads for four months and six days, but they are always shut. Too often with such confections, the caramel is right and the chocolate has a satisfying bite, but it all sits on a terrible bed of floury, dry shortbread that collapses onto the floor after the first nibble. Not this stuff. It has a real snap to it, is slightly bronzed, and you can feel the butter that holds it all together gently melting as it goes down.

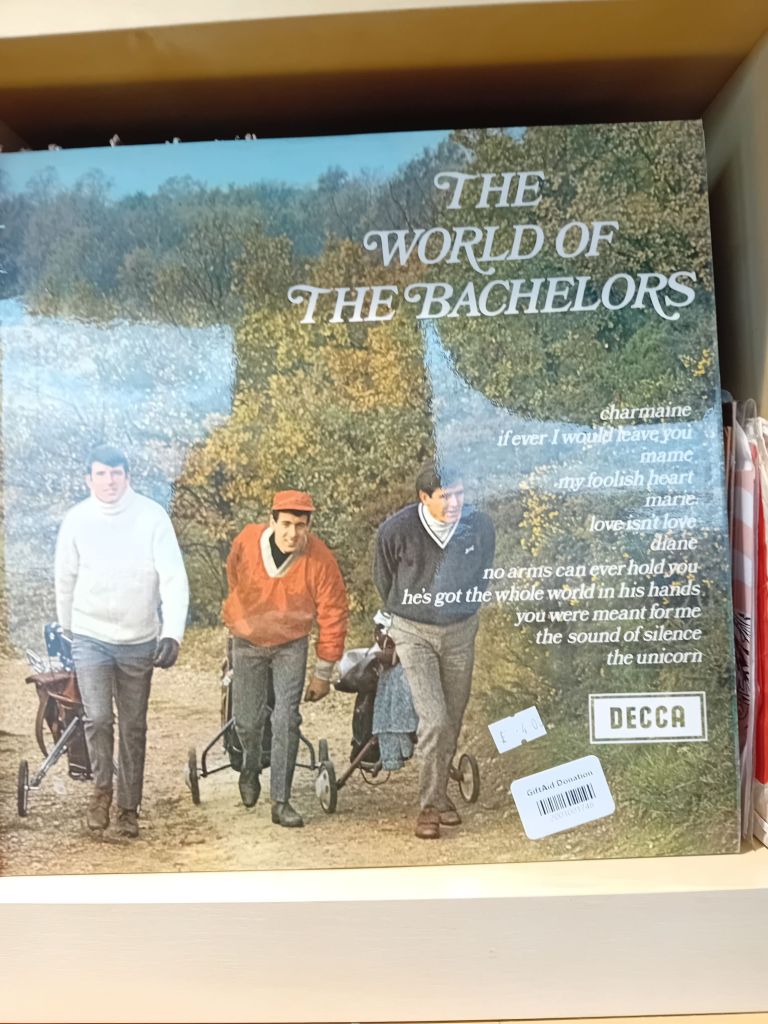

We pop into the Craignure charity shop, which always has cheerful older staff waiting with a smile. They are stocked mostly by people dropping off things they no longer need at the end of their holiday, just before getting on the Oban ferry, which you can see pulling in through the glass front door. The good thing about this shop is that they don’t look things up online to see if they’re ‘designer’. Nor do they check labels to see what material an item is made from. This means that a jumper—any jumper—is five quid. A T‑shirt is three, and books are one. This reintroduces the possibility of finding a genuine bargain, a pleasure sadly gone from the charity shops of the Cotswolds, where everything is picked over before display and priced so that, if you do find something decent, it is deflatingly expensive.

Our next stop is the commercial timber pier at Fishnish. I’ve been tipped off that a client has failed to collect a stack of logs and that they might be available. The chap I spoke to said they’ve been sitting there a while, so I want to check whether I’m about to buy 100 tonnes of rotten wood or beautifully seasoned fuel. There’s nobody around to ask which particular stack it is, so I wander about under the large cranes and make an educated guess based on colour. Timber, like most things, has doubled in price over the last few years, but it’s still much cheaper than relying solely on mains electricity. We use a mixture of both.

We finally make it to the tip. We have all sorts of stuff and want to put the right things in the right skips. I tap on the window of the office cabin and disturb what appears to be the only member of staff. With his cerebral palsy slur and strong accent, he’s very difficult to understand. ‘So it all goes in that one?’ I ask, with some surprise. ‘Aye,’ he replies, already on his way back to his station. We try to be more discerning anyway, separating wood and metal.

A chap pulls up in an estate car and two energetic Labradors bolt out. The somewhat obvious, but nonetheless enjoyable, conversation ensues about whether he’s come to leave the dogs at the tip. ‘It won’t be long if they keep eating the lounge and shitting on the shag‑pile rugs!’

Fortunately, the reward for doing the tip run is the Mull Cheese Farm, a quarter of a mile down the road. Unfortunately, like many things on the island, most of it is mothballed for the winter and only a small selection is available in the already modest shop. Still, it’s a beautiful place, and one we’ll return to when the tourist season is in full swing.

Tobermory offers a similar experience. Most shops are shut. The obligatory beach sauna stands frigid at the back of the car park. The gaily coloured frontages of the high street don’t quite compensate for the fact that we can’t get a bag of chips for lunch. The pub is open, however, and the Slovenian barman pours pints and takes food orders while a scattering of patrons either sit pensively toying with beer mats or passively engage with a tennis tournament from a former Soviet republic playing on the large TV screen.

We pop into Browns, which is a real treat. Remember those hardware stores that used to sell everything, before being taken over by such hideous things as Wilko and Home Bargains? Browns sells, in no particular order, hard liquor, ballcocks, tea strainers, referees’ whistles, dog jackets, laminators, binoculars, snooker cue chalk and ham. Sadly, it doesn’t stock fuel‑hose connectors for small outboard motors, which is what I went in for.

The return journey is punctuated by a one‑and‑a‑half‑hour stop in Craignure to get the tyres fixed. It’s hard to fill this kind of time, as everything apart from the Spar is shut. We do several circuits of the aisles and buy unnecessary food items purely to pass the time.

Back on the road, we do a quick calculation and realise we’ll get back to Knockvologan at exactly high tide. Having parked up and done up every available button on our coats against the wind, we guide ourselves by the dim light of our phone torches down to the narrows. We take off our boots, socks and trousers and wade into the dark sea. It reaches halfway up my underwear before I make land on the other side. No worries, though. Within twenty minutes we’re home, lighting fires and getting dry and warm again.