Every year a group of teachers from the mainland come to Mull and give workshops to the kids. Subjects include traditional music and dance. We had heard that some of them would be at the Bunessan Inn this evening, so we thought we’d pop along. It has been noted that we are long overdue a community outing, and that this would be a perfect opportunity to eat some deep-fried food and build connections with the wider community.

Of course, as regular readers will know by now, popping down to the pub involves checking the WillyWeather app to see how high the tide is, so we can actually get off the island and back on again at roughly the times we want. The last two outings have ended with boots, socks and trousers off, wading through thigh-high, punishingly cold sea to get back home. Tonight looks more benign, save for the gale-force easterly wind.

Two of my Christmas presents make life easier when making the trip from the street, across the narrows and up to the minibus at Knockvologan. First, the head torch (thanks, daughters!) turns pitch black into what looks like a slightly overcast day. Others cower back into the darkness when I turn to talk to them, such is the power I now possess. Not great for conversation, but excellent for avoiding the boot-devouring bogs that punctuate our route. Second, my new waterproof coat (thanks, Mum!). This bright, 1980s, orange-squash-coloured item (a colour described by a close neighbour as horrific) is totally waterproof. Not a light-shower-in-the-Cotswolds waterproof, but a barrage-of-seawater-on-a-commercial-fishing-vessel waterproof: nothing gets through. It is also completely windproof, which is more pertinent tonight.

We reach the minibus and there is real concern that the hinges of the doors might rupture, so we hold them steady as we climb in. There is a collective sigh now that we are out of the wind, and we change from our wellies into our civilian trainers and shoes. Bunessan is about twenty minutes away and, unusually, we don’t have a list of things to do on the way, so we just drive straight there. As always, I am the designated driver, as no one else can drive or get insurance for the bus. Slightly frustrating at times, but cheaper.

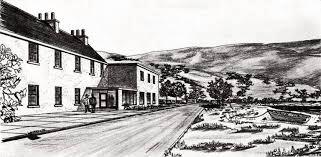

The Bunessan Inn is, apparently, 300 years old and was frequented by Dr Johnson and James Boswell when they were trying to track down some decent whisky. The website says they failed in their endeavour, as all the good stuff had been drunk two days earlier at the funeral of a popular local chap. That’s the story the Bunessan folk tell, and they are sticking to it.

It has a more modern feel on entering. There is an open fire in the smaller bar, but when you walk through the portal you are transported into the 21st century — or at least the late 20th. The dining area might feel familiar to those who visit relatives in retirement homes. However, to the rear, the modest bar area is dominated by two oversized Tennents taps, and beyond that is the pool table and darts board that provide some of the only live sport south of the Mull Rugby Club in Craignure. After being served a pint — and, not to labour the point, but for general H&S information, my only pint — we are shown to our table. We talk about holding hands and blessing the meal but decide that, despite it being common practice on Erraid, and having watched The Wicker Man last week, we will simply raise a glass to being around a different table together.

The battered haddock is the size of my forearm with my hand extended. The chips are chunky, though not especially crispy. It’s clear that the normal clientele may chat and pick around certain garnishes and relishes, but we fall to with little talk and great focus. When we have finished, the middle-aged waitress says something I haven’t heard since my teenage years around the table at Nana’s house: “It’s so lovely to see nice clean plates.” Indeed, everyone has eaten every last morsel. The token side salads are gone and even the sauce bowls look as though they have been licked clean. The sticky toffee pudding for afters (a “nice clean plate” being a prerequisite for pudding at Nana’s) is dispatched in similar fashion.

The music starts with an accordion and grows into a modest gig with a keyboard, a couple of fiddles and a snare drum. These look and sound like locals, not the polished professionals from the mainland. Once someone remarks that all the tunes sound like the theme to Captain Pugwash, I can’t hear anything else. Archie tells me there are bagpipes on the floor next to one of the players, which I can’t see due to the large pillar obscuring my view. Ten minutes later, halfway through an anecdote about an Australian cane toad, there is a sharp pain in my left ear, like the start of a migraine. My suspicions are confirmed: the bagpipe is an outdoor instrument.

It’s great to realise that we are slowly building up a group of friends who live and work on the Ross of Mull. Some we know through work they have done on Erraid, others through community events. I’ve never been one for networking, but I understand that here it is how things get done and how people connect socially.

There is a graph somewhere that depicts how much time it takes a certain number of people to leave a pub while having to say goodbye to a certain number of other people, possibly taking into account alcohol consumed. Being the driver, I have leverage here and, after five minutes of milling around waiting, I stride purposefully towards the exit. The message is clear. I swing out of the car park and someone mentions that Archie is still inside. I do the old pulling-off trick when he approaches, which amuses the slightly intoxicated passengers.

Back at Knockvologan, the wind has dropped and it is a pleasant walk back onto the island, with minimal wading. We are all back in our snug little cottages by eleven, which is a late one for us.